Vaila Hornsby

Air Pollution: Cause and Effect

Concerns regarding air pollution in the UK are long standing. For instance, approximately four thousand people are thought to have died from respiratory illnesses caused by the combination of smoke and sulphur dioxide (SO2) in the air during the Great Smog of London in 19521 . In response to this crisis, the Clean Air Act 1956 was enacted, banning the use of coal in both domestic and industrial fires2. However, although the implementation of this key piece of legislation has ensured the reduction in smoke and SO2 emissions, as our modern society has evolved new origins of air pollution have arisen. A principal example is the toxic emissions of motor vehicles which, according to Transport Scotland, contribute towards 69% of the total transport greenhouse gas emissions in Scotland3. Therefore, air pollution is still very much considered an ongoing concern in today’s modern society.

What is Air Pollution?

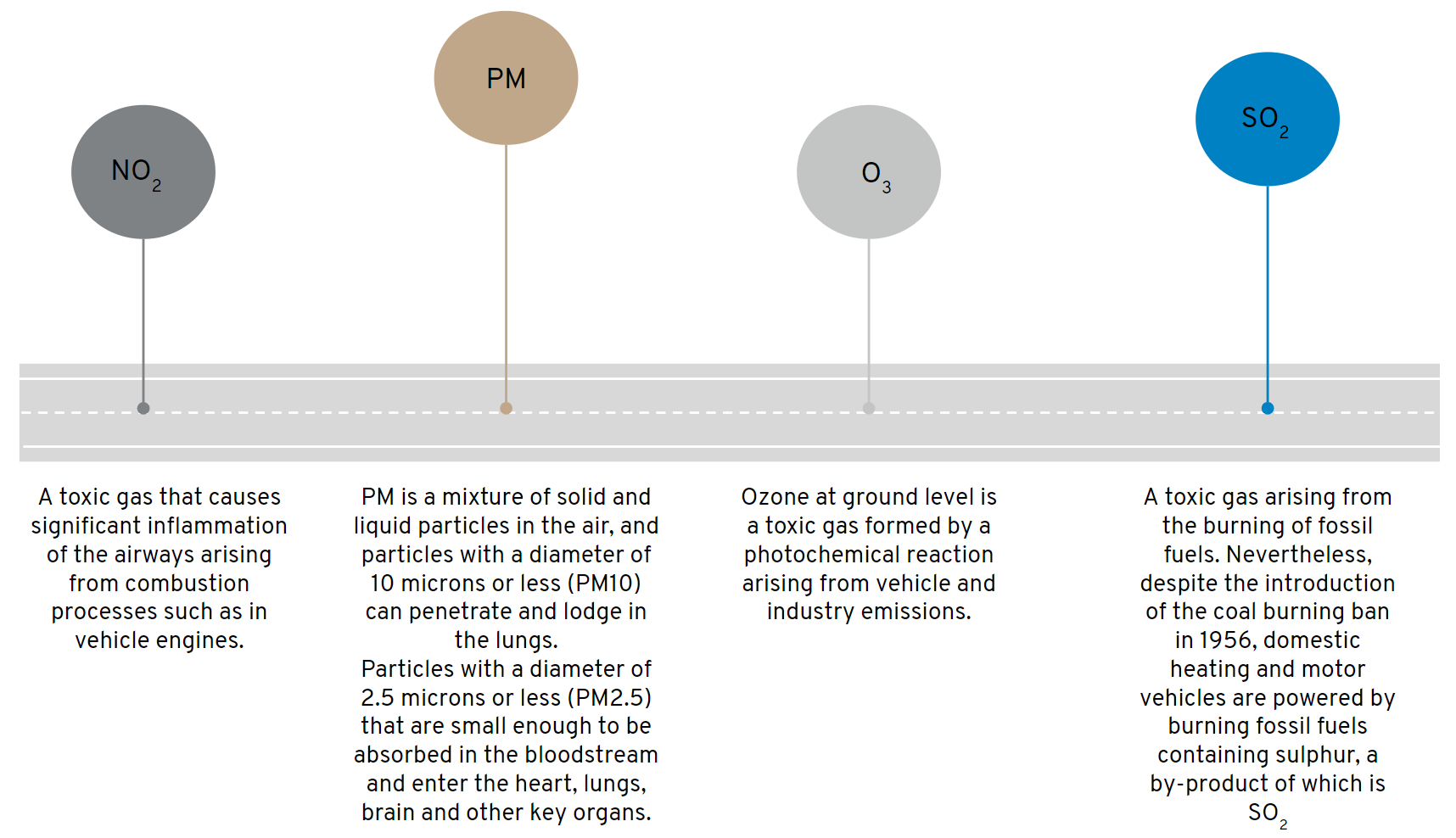

The World Health Organization (“WHO”) identifies outdoor air pollution as a “major environmental risk to health,”4 affecting countries across the world. The harmful chemicals arising from motor vehicle air pollution are primarily described below:

Consequently, the concentration of these chemicals is most apparent in cities where there is a high volume of traffic5. According to WHO, the health effects of these toxic chemicals in the air trigger asthma and cause breathing problems in the short-term, with long-term effects comprising reduced lung function growth and the development of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases such as lung cancer6. Conversely, as air pollution is commonly linked to car vehicle emissions, there is a heightened risk that city inhabitants will be affected by the detrimental effect of low air quality due to the greater concentration of cars in cities. If air pollution therefore presents such a serious threat to the health of those living in areas of low air quality, what are the repercussions for those exercising in these polluted urban environments?

City Running: impacting health and performance?

As part of their air pollution recommendations, the WHO do not advise exercising outdoors in areas with increased air pollution7. In particular, it is believed that outdoor city runners are more at risk of developing respiratory health issues as running is an aerobic activity8. Therefore, the reason for this increased risk is a physiological one: during periods of aerobic exercise, runners breathe more deeply and inhale larger quantities of air, placing them at a greater chance of inhaling harmful chemicals9.

Consequently, it appears that the benefits of outdoor running are overshadowed by the dangers associated with air pollution in urban areas of low air quality.

Scotland’s city air pollution levels

For those aware of its natural beauty, Scotland often invokes images of wild mountain ranges, dark green forests, and deep, bottomless lochs. It is therefore surprising to learn that several of Scotland’s cities have high levels of air pollution. The WHO recommends that as an absolute minimum, air pollution levels in urban cities must not exceed:

- An annual mean of 40µg/m3 for NO2;

- An annual mean of 20μg/m3 for PM10 and 10μg/m3 for PM2.5;

- An 8-hour mean of 100μg/m3 for O3; and

- A 24-hour mean of of 20μg/m3 for SO2.

However, many countries are struggling to meet these targets with national air pollution regulations failing to align with the minimum WHO recommendations. For instance, although the European Union (EU) Air Quality Framework Directive 2008/50/EC (“2008 Directive”) sets legally binding limits for concentrations of harmful pollutants in outdoor air, these limits do not comply with the WHO guidelines10 The EU air quality limits were incorporated in the UK with the implementation of the Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010, but as these limits do not align with the WHO recommendations, even if the minimum air pollution limits are observed there is still a substantial risk of harm to public health.

Since 2012 Hope Street, Glasgow’s “most polluted street”11, has consistently averaged at an NO2 annual mean over 1.5 times the limit of 40μg/m3 12. Other streets in Scotland’s cities including Edinburgh’s Nicolson Street13 and Dundee’s Seagate14 have continuously breached the annual mean limits for NO2, most recently in 201915. Consequently, despite the vast expanses of green space in the wilds of the North, Scotland’s cities are struggling to comply with air pollution regulations, presenting a significant risk to the health of those who actively run in these polluted environments.

Investing in Cleaner Air

In 2020, Scotland’s air pollution levels fell for the first time within the legal limits16. This compliance with the regulations can be attributed to the Coronavirus lockdown measures imposed in the months of March to May where Transport Scotland reported a significant decrease in car travel as the country was instructed to stay at home17. However, with the lifting of lockdown restrictions, air pollution levels began to rise as travel was again permitted18.

This brief period of fresh air illustrates the direct link between car travel and pollution levels and displays the potential for investments clean city air. The Scottish government has so far actioned this in the following ways:

Low Emission Zones (LEZs)

- Implemented in four of Scotland’s major cities before being halted by Covid-19 pandemic.

- Restricts city-centre access to only the ‘cleanest vehicles’.

Edinburgh’s ‘Million Tree City’ by the end of 2030

- A global warming mitigation approach that helps to reduce air pollution in the city.

- Planting of certain species of trees alongside roads acts as a natural barrier and filters pollutants arising from vehicle emissions.

The Scottish government has the 2021 objective to publish a new clean air strategy for Scotland that outlines interconnected measures to address air pollution, climate change, carbon reduction and mobility. This work builds on the independent CAFS review from 2019 and links with the UN Sustainable Development Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

Investing in clean city living and the technological adaptations required to realise such goals is a priority.

Sources:

- Bramble, D., Lieberman, D. Endurance running and the evolution of Homo. Nature 432, 345–352 (2004).

- Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, 2002. Air Quality in the UK. London: POST p.1

- Ibid3

- World Health Organization. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution.

- Ibid5

- Ibid6

- Flynn, S. and Rodenburg, M., 2020. How Air Pollution Affects Runners.

- Runners Connect. 2020. Does Air Pollution Affect Running Performance?

- Thompson, M., 2017. Physiological and Biomechanical Mechanisms of Distance Specific Human Running Performance. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(2), pp.293-300.

- For example, the 2008 Directive sets the following air quality limits: an annual mean of 40µg/m3 for PM10 and 25µg/m3 for PM2.5, an 8-hour mean of 120µg/m3 for O3, and a one-day mean of 125μg/m3 for SO2. Article 13(1) and Annex XI.

- Iqair.com. 2021. Scotland Air Quality Index (AQI) and United Kingdom Air Pollution | AirVisual.

- Glasgow City Council, 2017. Air Quality Annual Progress Report. [online] p.47.

- Annual mean of 50.4μg/m3 for NO2 in 2019.

- Annual mean of 44.5μg/m3 for NO2 in 2019.

- Scottish Air Quality Database, 2020. Annual Report 2019. [online] Ricardo Energy & Environment, p.27.

- Since their introduction in 2010. See Thomson, G., 2021. Scotland’s Most Polluted Streets in 2020. [online] Friends of the Earth Scotland.

- Friends of the Earth Scotland. 2021. COVID-19 restrictions mean Scotland meets Air Pollution legal limits for first time – Friends of the Earth Scotland.

- Ibid32